The Myth About Core Strength

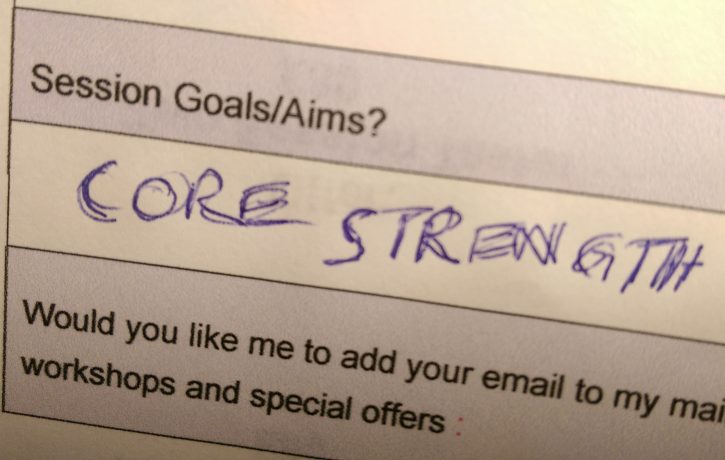

A goal many of my clients note down on their client form, when they come to see me is “core strength”. Probably not surprising, considering most of them come to me to practice Pilates, and Pilates is considered a discipline that improves core strength.

And yet, every time I see “core strength” as a goal on the form, I wonder what this means to the client. The truth is, this goal does not actually tell me much about what you are wanting to achieve. My first question usually then is “What are you hoping to achieve through core strength?”

What is Core Strength?

The thing is, that core strength is not actually a goal in itself. It is a concept, an idea, a theory about the body’s biomechanical function. If you are interested in physical fitness or rehabilitation of the spine, you have most likely heard of core strength. It gets referred to as a solution for many problems. Apparently, a weak core can cause back pain and spinal problems. A strong core can keep injury away and enables you to master more challenging physical tasks. We talk about core strength as though we all agree on what it is. The funny thing is, we really don’t!

We can somewhat agree that the core refers to the centre of the body and strength refers to muscular strength. So it makes sense that we are talking about the strength of the muscles surrounding the spine in the centre of the body. However many professionals including Physiotherapists and some Pilates Teachers are very strict in differentiating between true core muscles and global trunk muscles, which should not play a role in core strengthening exercise programs.

This is where the first problem lies. While for some of us it is crucial that only four deep muscles of the trunk are to be considered the core, for some it is six and for others it is every muscle surrounding the center of the body. Which muscles you consider to be a core muscle makes a huge difference in how you go about strengthening your core. If you believe in the four deep core muscles (diaphragm, transverse abdominus, pelvic floor and multifidus) for example, you would use a very particular strategy. The idea is that these deep muscles are postural muscles, that play a key role in stabilising the spine in a neutral position. As soon as we add movement of the trunk into flexion or rotation for example, we would start exercising the global muscles of the trunk. If the core is considered weak this would mean that the goal is to strengthen the deep muscles in isolation. So we would do minimal effort stability exercises with no spinal movement.

If we believe the core is the body’s center in general and all muscles in this area play a role in spinal stabilisation we would do more classical abdominal, or bracing exercises that feel a lot stronger and give you that six pack as a bonus.

What To Believe?

So we have to decide which core strength idea to believe. How do we go about making this decision? We could try to find out more about the research that has been conducted in the area of core strength. However you would find that there is equal research supporting both theories. Paul Hodges has been studying the deep core muscle theory for many years and Stuart Mc Gill has written many books about his reasons behind his abdominal bracing idea. Also, there is a lot of research, rejecting the whole idea of core muscle strength. Those who do reject it argue that the body does not create stable, healthy movement by contracting individual muscles like pulling strings on a marionette. Rather movement and stability are created by something more along the lines of tensegrity, an architectural construct that suspends leavers in an equally stretched and tensioned elastic network.

So we are talking about core strength and we work on improving core strength. Yet no one actually knows what we are talking about and what we should be doing.

My Approach

I have experience with the different core strength ideas out there and there is a time and place for all of them. Personally I find I need to learn more about your reasons behind your wish to improve your core strength, before I know how best to help you. I ask you, what do you want core strength for? Did someone else tell you, that it would help you eliminate pain or improve your physical abilities? Do you feel it would give you a more toned waist? Do you just want it because everyone seems to want it? What are you hoping to gain from core strength truthfully? The answers to these questions may already give me a more clear idea of what approach to take. The rest will come from observing you move, so I can see the supposed lack of core stability for myself. If there is such a deficit, it may present itself in very different ways, which yet again will influence the approach.

I would also argue that no body part is more important than another. Our bodies have developed over thousands of years to be durable and efficient. There is no design flaw. In some of us, because of our modern life habits or medical history, there may be a lack of what I prefer to call “core control” (efficiency and appropriate stability of the trunk during movement) or “motor control” (coordination and stability of efficient movement patterns, facilitated by the nervous system), which may impact on our spinal health or abilities. However the physical reason for this lack of control will be very unique in each person, which means the strategy we use to improve it will be unique too.

There are a vast amount of ways in which we can influence core control. Connective tissue experts like Thomas Myers and Robert Schleip have made us aware of just how interconnected the inside of our body is. Connective tissue, called fascia interwebs our muscles, organs and bones from foot to brain. The idea that we should isolate one or a few muscles by trying to contract them individually and locally suddenly seems very unrealistic. Sometimes we may lack core control because of a local weakness or injury indeed, but how are we going to work a muscle in isolation that is entirely interwebbed with others?

We can in fact use the interwebbed structures in our body to improve core control. How did we first learn to move well and control our centre of gravity? How did we first learn core control when we started crawling and walking? We engaged with our environment. We used the feedback we got from the floor, from gravity, from furniture we pulled ourselves up on. It makes sense that we use the same strategies to maintain and to brush up on our core control later on in life. You could call it re-engaging with our natural instincts to learn how to move well.

The Pilates apparatus, such as the reformer, trapeze table and combo chair are fantastic tools for this. The machine gives you a unique experience of movement. It gives you subtle resistance and support. It gives you feedback and enriches your neurological connections into your muscles, as it lets you explore movements in different relations to gravity. What ever is aiding core control inside your body is getting lots of stimulation here. It is my job to not only guide you through the movements and with the use of the machines, I observe the quality of your movements in all areas of the body, from the alignment of your lower extremities, your head, neck and shoulder organisation into the articulation and control of your spine. All of this is valuable information about your core control ability as well as many other elements that play a role in healthy physical movement ability.

Core strength, if it exists, is not a one fits all cure to everything. What is most important to me is what you actually want to achieve. What do you want your body to be able to do? What do you want to change and what will it mean for you and your life when you achieve it? Some idea of core strength might indeed come into play. But it will be unique to you and your goals.

If you would like to try Kristin’s approach to core strength, you can discuss your case with Kristin at The Body Matters on 01702 714968.

- The Thing About Mixed Feelings Is… - 4th June 2023

- Overthinkers – Here Is What You Really Need To Know - 28th April 2023

- Why Emotions Can Be Overwhelming - 13th December 2022