in Joints & Muscles, Sports Physiotherapy

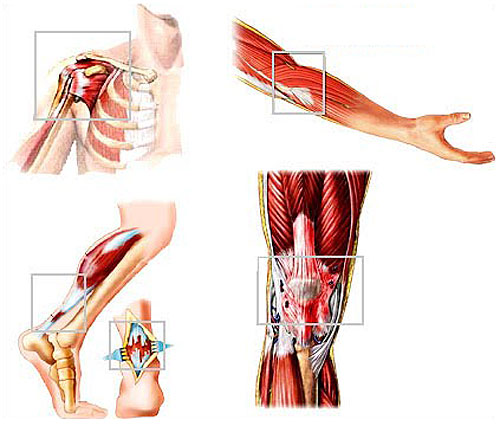

What is Tendinitis or Tendinopathy?

Tendinitis has become a common issue affecting between 6 and 17% of the population and is one of the most common pain conditions in the sporting population. The problem is, the name tendinitis has now become obsolete because the condition itself is now not deemed to be an inflammatory condition ( any condition with “itis” at the end infers an inflammatory basis to the pathophysiology).

A more appropriate name is tendinopathy, which is a broad term used to describe predominantly degenerative conditions that cause pain, swelling, weakness, and stiffness of the tendon.

Although the cause of tendon pain is not fully understood it is generally thought that repeated overloading of the tendon via muscle overuse, causes degeneration and disorganization of collagen fibres, thickening of the tendon, and causing neovascularization (new blood vessels) and new nerve endings in the expanded tissue. This is known as tendinosis.

Tendinopathy is thought to develop when there is an imbalance between the pathological changes and the regenerative changes that occur in response to injury.

Possible complications and progression of tendinopathies include tendon rupture, time off work, and decreased participation in sports.

The diagnosis of tendinopathy can usually be established on clinical grounds alone, without the need for an ultrasound or MRI.

Pain and stiffness are typically worse first thing in the morning and is usually felt after exercise but may also occur during exercise. Sufferers tend to experience pain at the beginning and the end of the training, with a period of diminished discomfort in between.

On examination, the affected tendon will be tender to touch and there may be visible or palpable thickening of the tendon and/or the point where the tendon inserts into the bone: although these physical changes are more common in the chronic phase.

Appropriate therapy in the management of tendinopathy will include massage of the affected tissues and joint mobilisation as well as connective tissue stretches and identifying muscular compensations and joint restrictions, further away from the site of pain. For example, tendon issues at the elbow can lead to aches and pains around the shoulder and upper back. These types of compensations really benefit from manual therapy and the release of the restrictions and muscle tension.

It is important to understand that in the majority of cases the symptoms will resolve between 3 and 6 months, however, underlying causes and contributory factors should be identified and managed in order to prevent the condition from becoming chronic ( longer than 6 months).

10 minutes of ice ( if an ice pack is not available a bag of frozen peas can be used as an alternative) applied over the area is appropriate during pain episodes, such as after exercise.

Simple analgesia (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) can help sometimes for pain relief.

An initial period of rest, or relative rest (stopping high-impact activities, such as running), is appropriate until the pain subsides but complete prolonged rest is counterproductive if it is. Full activities can then be resumed as pain allows.

An appropriate daily programme of tendon stretching exercises and strength training should be prescribed. Clinical studies have consistently identified benefits from an eccentric exercise programme. An eccentric muscle contraction is a type of muscle activation that increases tension on a muscle as it lengthens which typically occurs when a muscle opposes a stronger force, which causes it to lengthen as it contracts. This is typically performed daily for up to 12 weeks or until the pain resolves.

A biomechanical assessment can be considered by an appropriate professional e.g. an Osteopath, Sports therapist or physiotherapist. Orthotic heel-lifts, a change of footwear, and custom-made orthoses which may correct misalignments in the foot and other supports that take the pressure off the tendon are easily obtained and can help ease the symptoms in other areas of the body.

Referral to a sports physician or an orthopaedic surgeon after 3–6 months is a possibility if the response to initial conservative measures and manual therapy and exercise is inadequate.

Treatment options from specialists include:

Physical therapy treatments such as iontophoresis (topical introduction of ionized drugs into the skin using electrical current), phonophoresis (ultrasound-enhanced delivery of topical drugs), and low-level laser treatment have demonstrated some efficacy in treating tendinopathy, but the evidence appears to offer limited success rates.

Extracorporeal shock-wave therapy is a treatment method that has been successfully demonstrated to help to heal in medical studies but can be expensive and painful in its application which can put people off.

Surgical techniques include the excision of fibrotic adhesions, removal of tendon nodules and making longitudinal incisions in the affected tendon to stimulate healing in the tendon.

If you would like to discuss tendinopathy further, please contact www.thebodymatters.co.uk on 01702 714 968.

- Deepen Embodiment: Somatic Breathing with the Realization Process - 20th June 2025

- How Massage Transforms Muscle and Physical Health - 16th May 2025

- What is Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)? - 29th April 2025

-

Pingback: Prevention and Treatment for Runners Knee - The Body Matters